From negative to positive

16 July 2018

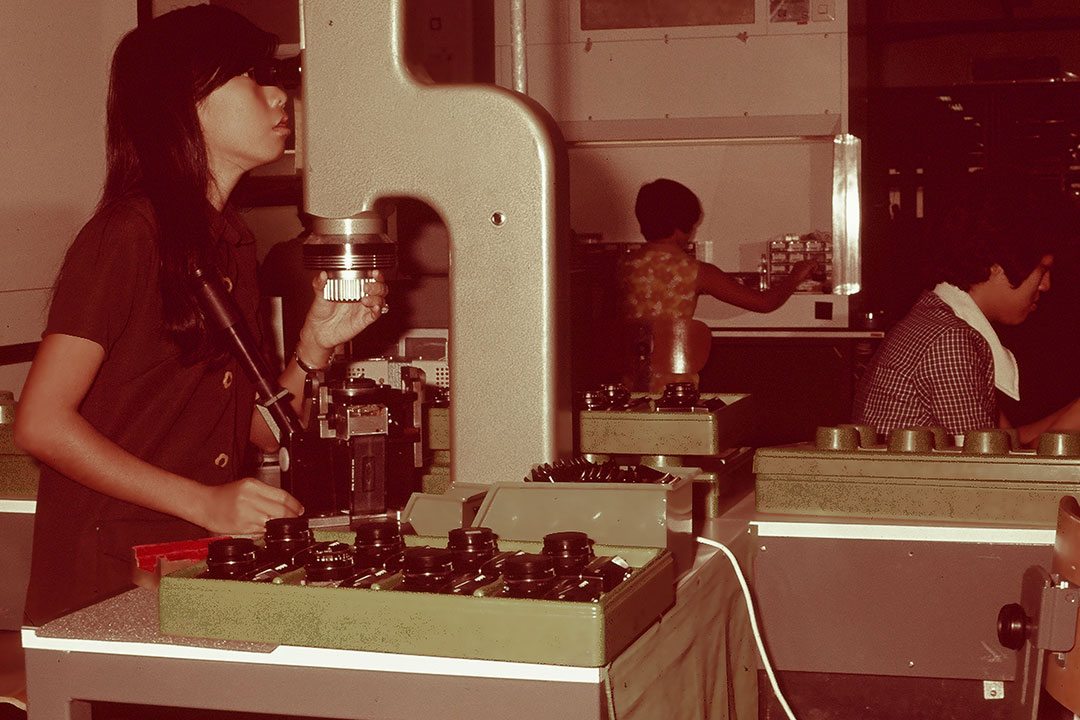

In the 1970s, Singapore workers were producing what some would say were among the best cameras in the world. Singapore had successfully wooed German camera maker Rollei to shift its production capabilities here in 1971. This was made possible because DBS helped by financing the company.

Rollei’s entry created thousands of jobs for Singaporeans and crucially, shifted the Republic from low-wage industries to higher-technology ones. In 1981, Rollei’s parent company in Germany went bankrupt and the factory here shut down. This left the Republic with 4,000 workers who were highly trained in precision engineering, creating a valuable base for the disk industry that began in Singapore in the 1980s.

Ang Kong Hua, who was among the pioneering team that joined DBS from the Economic Development Board (EDB), shares his memories of bringing Rollei to Singapore.

From negative to positive

One of the most important transactions that DBS made in the early days was the financing of German camera company Rollei in Singapore.

I was the officer who had to deal with that. I went to Germany, visited all their plants, and did all the project work.

The tie-up was initiated through the EDB. In those days, the EDB was sourcing for investments from Europe and the US. DBS’ role was to assist in the financial aspects – with loans, financial incentives, training grants etc.

I flew to Germany to compile a report on Rollei’s operations. I visited their factories, R&D facilities, assembly lines and offices, so we could figure out how much the company was worth and its investment potential.

To be honest, we were all young at the time, still learning on the job, and had very little experience. Today, if you ask me to go to inspect a plant, it will be a different story.

Rollei’s entry into Singapore in the end turned out to be very significant. Rollei was the reason Singapore developed a very high competency in precision industry activities.

It was the origin of our entire tool and die sector capability, because Rollei, in partnership with the Government, also set up trade schools – that created and trained many tool and die engineers, optical engineers and craftsmen. It also built Singapore’s capabilities in precision machining and precision manufacturing – skills that were non-existent in Singapore at the time.

It was a national push for Rollei to come to Singapore. But if DBS hadn’t invested, Rollei wouldn’t have come. No other institution here could have done the kind of financing required. And Singapore needed them to create jobs here.

We knew they were also coming here to save themselves. They were dying in their home country: their labour costs were too high, and the Japanese were killing them in the market. They weren’t going to survive long. They came to Singapore to dramatically reduce their production costs to get back into business. It worked in a way. I think it prolonged their survival.

DBS took a huge risk on Rollei. There was almost no security if Rollei had collapsed, except the physical factories that our money was used to build. But the factories weren’t worth so much, and I think the bank took losses when Rollei eventually shut down.

Still, the people who had trained and worked with Rollei went on to become entrepreneurs or critical persons in the burgeoning industries that became vital to Singapore’s growth. One example was Amtek Engineering. If you trace Amtek’s roots, it goes all the way back to Rollei. Their initial key people and founders were ex-Rollei people. That’s how far-reaching this investment was.

Ang Kong Hua was part of the original team that left EDB to start DBS in 1968. In his six years with DBS, he was responsible for establishing the Corporate Finance Division. He was Chief Executive Officer of NSL (formerly NatSteel) from 1974 to 2003, and its Executive Director until 2010. He served as a DBS Director from 2005 to 2011. He is currently Chairman of Sembcorp Industries and sits on the board of GIC Pte Ltd.