The next time you are about to throw out your handphone to get a new model, perhaps ask yourself first: How many gorillas died for this?

What is the link, you might ask? Well, the critically endangered Grauer’s gorilla has lost 77 per cent of its population in the last 20 years, partly due to the mining of minerals used in mobile phones.

The main mineral mined is coltan, a type of ore used in mobile phones and other electronic devices such as laptops, digital cameras and tablets.

And despite the hard labour (often in slave-like conditions) involved in mining this mineral, and the devastating impact that this has on the natural habitats of various wild creatures, we throw aside our devices each time a new version comes along.

Experts cautioned that the rollout of the fifth-generation (5G) mobile networks could also spell the demise of 4G gadgets, and see them ending up on the trash heap.

Tech gadgets are being produced in greater quantities and varieties everyday. And in the consumerist race for the shiniest, newest models, older devices are often simply chucked down the rubbish chute.

Environmental experts have for some years warned about the perils of electronic waste, or e-waste, which not only takes up space in landfills but can be toxic too. But our pile of e-waste is only set to grow.

Singapore is already a major culprit of e-waste

Given how much we love our gadgets, it may not come as a surprise that Singapore, alongside Hong Kong, is the top producer of e-waste in Asia.

A 2016 study by global think tank United Nations University (UNU), put Singapore’s e-waste at 137,000 tonnes in 2015.

A study commissioned by the National Environmental Agency (NEA) between April 2016 and October 2017, meanwhile, found that Singapore generates about 60,000 tonnes of electronic waste each year.

More detailed figures will be available after the implementation of a regulated e-waste management system in 2021, said NEA in response to TODAY's queries.

Currently, only about 6 per cent of the e-waste we generate each year is recycled, while about 25 per cent is thrown out with food and other general waste.

Minister for Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli said in August last year that people have underestimated the issue of e-waste for years and it has become a more pressing problem than plastic waste.

He added: “E-waste is very toxic, people underestimate the toxicity of the e-waste that we dispose of and for the longest time we weren't processing it.”

When not discarded properly or mixed with general waste, toxic materials in e-waste — such as heavy metals and mercury — contaminate the incinerated ash when general waste is burned and landfilled.

These toxins not only enter the soil, but also seep into the water, polluting it.

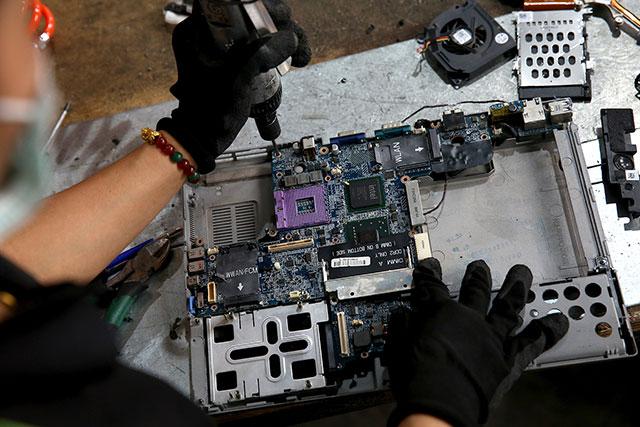

A worker at e-waste recycling firm Virogreen dismantles a server. Virogreen said the number of electronic devices it collected in Singapore jumped from about 86 tonnes in 2016 to about 360 tonnes in 2017. Photo: Nuria Ling/TODAY

The chase for the latest tech is killing those gorillas

Rising affluence, consumerism and electronics that are “designed to fail” have resulted in an increasing rate of e-waste disposal in recent years, said Professor Seeram Ramakrishna, the chair of the Circular Economy Taskforce at the National University of Singapore.

Products that are “designed to fail” refer to the concept of “planned obsolescence,'' where manufacturers design new tech products with limited useful lifespans, so that they become obsolete — either unfashionable or no longer functional — after a certain period of time.

This compels consumers to fork out more money on even newer products.

This has become embedded into our consumption habits that today, and consumers have become more likely to interpret working electronics as insufficient or unusable, Prof Ramakrishna said.

No surprise then, that e-waste has become “the world’s fastest growing waste stream”, according to a report by the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE), a group of private and public sector leaders with the goal of driving organisations to adopt circular economy strategies.

Consumers TODAY spoke to said they do try to use their electronics for as long as possible. Still, engineer Alvin Koh said it can be difficult not to buy into new trends, as tech products are increasingly seen as status symbols.

The 29-year-old said: “It’s part of the materialistic and consumerist mindset. It's seen less as a tech product and more like a fashion trend to have a new phone, for example.”

But some are starting to opt out of this consumerist culture. Mr Chiang Ling Yi, 28, a senior data analyst, said: “I used to be quite passionate about the latest technology but I’ve begun to ask myself what I really need, because I feel like I don’t have time to use so many devices.”

“I might not even use it enough before it becomes obsolete,” he added, citing an example of how the makers of electronic running accessories constantly release new versions.

“I upgraded from a basic to a more advanced Garmin device within the span of a year, and now they have already released a newer model with new functions — solar power features — again,” he said.

A training session for volunteers at Repair Kopitiam, a community-run group that teaches people how to fix their spoilt electronics. Photo: Najeer Yusof/TODAY

The spectre of 5G

The current stream of e-waste could turn into a flood, as people are expected to start dumping smartphones, modems and other gadgets incompatible with 5G networks, once these go live.

“The immediate effect will be an increased number of older devices that will be discarded and substituted with 5G compatible-equipment,” said Mr Paolo Facco, a project manager and solid waste management engineer at GA Circular, a consultancy specialising in food and packaging waste.

While devices will not “suddenly turn obsolete”, they will be unable to support the 5G technology, causing a “gradual but tangible impact” on waste. Given consumer trends and preferences, one can expect a net increase in the amount of devices sold per year and in the long term, said Mr Facco.

What is Singapore doing?

In March, the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR) made it mandatory for manufacturers of large household appliances — including refrigerators, air-conditioners, washing machines — to collect at least 60 per cent (in weight) of the appliances they supply to the market each year for recycling.

The collection target is 20 per cent for smaller consumer electronics such as lamps, portable batteries, and info-communication technology (ICT) equipment (printers, laptops, tablets, mobile phones and routers).

Some companies have also formed partnerships with recycling facilities to make it easier for their consumers to recycle their old products, such as the one between telco M1 and recycling firm Virogreen to set up e-waste collection bins in malls.

Some of the awareness-raising and corporate initiatives are bearing fruit. E-waste recycling firm Virogreen said the number of electronic devices it collected in Singapore jumped from about 86 tonnes in 2016 to about 360 tonnes in 2017.

One of the companies that sends its e-waste to Virogreen is DBS Bank.

“Before any of our e-waste is recycled, all of the logs and the configuration are deleted from the machines. We also remove the hard drives and delete any information that's on there before recycling,” said DBS’ chief procurement officer Donna Trowbridge.

DBS also encourages employees to reuse devices such as corporate handphones internally within the organisation. If a corporate phone is still reusable, the set is kept as a spare phone, or given to an employee who loses or breaks his, said Ms Trowbridge.

Challenges remain

Still, there are challenges in the way of a proper e-waste recycling infrastructure here.

The informal sector of scrap traders and rag-and-bone men, for example, creates disorganisation in collecting e-waste, said Mr Sharul Annuar, Marketing Manager for Virogreen Singapore.

Rag-and-bone men do not necessarily recycle the e-waste they receive, Mr Annuar noted.

He added: “Singaporeans have this ingrained mindset that you can actually sell e-waste to the karung guni men, so it's a challenge for us to convince them that there is a fee to recycling and it’s not free."

Some consumers TODAY spoke to said e-waste recycling could be made more convenient. Ms Van Koh, an Singapore Institute of Management student in her 20s, said, for example, that more e-waste bins could be set up in housing estates.

She added: “Seeing that a lot of e-waste comes from households, it would be easier if there were collection points in the void decks or housing estates. I’ve found it quite challenging because I don’t know where to send my gadgets for recycling… those that need to be thrown out usually cannot be resold, and so the most convenient way is to sell them to karung guni men or throw them away.”

A worker at e-waste recycling firm Virogreen dismantles a laptop. Specialised refineries can extract metals like gold, silver and copper from circuit boards. Photo: Nuria Ling/TODAY

What’s next?

Singapore can develop its “local capacity” for repair, reusing and recycling by integrating the numerous, easily accessible and often inexpensive electronics repair and resale shops islandwide, said Ms Amita Baecker, a project manager and business development manager at GA Circular.

Such a move would formalise the existing repair and reuse industry towards safer and more environmentally friendly practices, she noted. “(If) purely profit-driven, these business ́are not encouraged to handle the less valuable components found in e-waste, (so) larger volumes will bring economy of scales to them," she said.

And there is profit to be made in the e-waste business. Mr Facco noted that the potential value of e-waste in Singapore is an estimated S$234 million.

“Developing cutting-edge competence in the field of e-waste recycling technologies will also allow local businesses to lead the Asian e-waste industry, which accounts for 40 per cent of global e-waste generation,” he said.

Regulation should not only push manufacturers to collect and recycle e-waste, but also nudge them to think about how to reuse or turn materials into new products, experts said.

“Recycling is a fallacy if not complemented by robust systems to recover and reuse materials,” said Ms Maggie Lee, a market transformation manager at the World Wide Fund for Nature (Singapore).

This Trash Talk series is produced in partnership with TODAY.