How do entrepreneurs innovate to solve problems in a world that’s in constant flux?

Uncertainty has become the norm today. Rapid changes and technology advancements mean our lives could be markedly different in just a few years, or even sooner. This is “the era of the unknown”, says Prof Dr Ir Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, the keynote speaker at the DBS Foundation’s 2017 Social Entrepreneurship Summit.

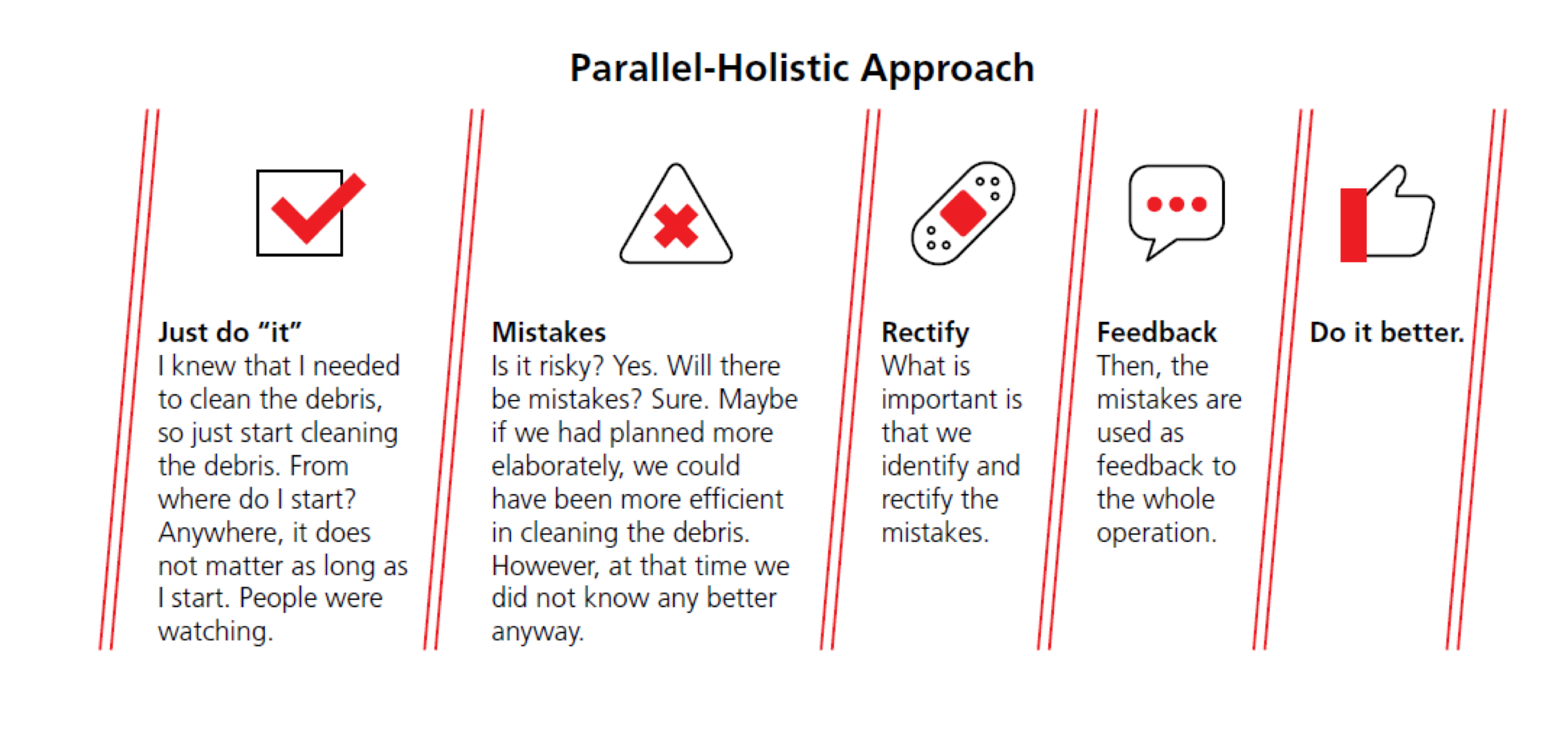

In his speech, Mangkusubroto shares his experience leading reconstruction efforts in Aceh and Nias after the 2004 tsunami, and how he got started from “deep in the unknown”. His speech is reproduced here.

I’ve been asked to address the topic of “Youth Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation”, where disruption and technology are key elements for this topic. Unfortunately, I do not think I’m the right person to address this topic because I’m a baby boomer – so far away from the millennials who are the key players of today.

So, rather than acting like a know-it- all and telling you how easy you have everything nowadays, I’m going to share some wisdom from somebody who has been around longer than most of you have.

When we talk about entrepreneurship and social impact, we are basically talking about somebody who is making something on their own and making it sustainable. And the impact of this something is beneficial to the society.

The driver is this “somebody”. So, we need to understand in what kind of environment is this somebody living to know how to best support them.

I will talk about “living with and loving the unknown”, which sets the environment we are living in currently. This is especially important for youth because you will continue to be living in an era where the world’s unknown, uncertain and unpredictability is always the norm.

The world is changing rapidly and our advancements in technology are at the point of no return, and will continue to advance so that we won’t know how different our lives will be a few years from now or for that matter even next year.

Hariri (a well-known historian of the history of mankind) predicts that AI will create a useless class of humans. We must be aware that a big revolution is to come. This change will be so rapid that in just 10 years, the biggest market capitalisation will have shifted from oil & gas and finance industries to the tech giants. Who could have predicted this just 10 years ago?

The next era is of human-machine entrepreneurship. The key findings in an era of human-machine partnerships predict that:

- An estimated 85% jobs in 2030 have not been invented yet, e.g. in Indonesia just a couple of years ago, the profession of a Gojek/Uber/Grab driver was unknown.

- The ability to gain new knowledge will be more valuable than the knowledge itself.

These findings scream “THE ERA OF THE UNKNOWN” louder than ever.

We need to start living what Socrates had pondered upon years ago, that the best approach to deal with the phenomenon is from a place of knowing nothing.

When you see a social phenomenon and you think you know all about it, it makes the way for failed interventions.

We should revisit the term “best practices” in solving a social problem. For years, it is shown that the best practices have not been effective in providing sustainable solutions. For example, in general the best practice of forest management was not to let anyone live in the forest, at least in Indonesia. This has resulted in certain indigenous groups being deprived of their centuries-old way of life, and later plunged them into the depths of poverty in urban areas. It took so much effort until finally the Indonesian Constitutional Court recognised the rights of indigenous groups to their customary forests.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong India

India Indonesia

Indonesia China

China Taiwan

Taiwan

2 Feb 2018 by

2 Feb 2018 by