breaking-new-ground

Breaking New GroundThe early tech adopter: Tales of DBS’ analogue ambitions

By DBS and The Nutgraf, 2 Aug 2023

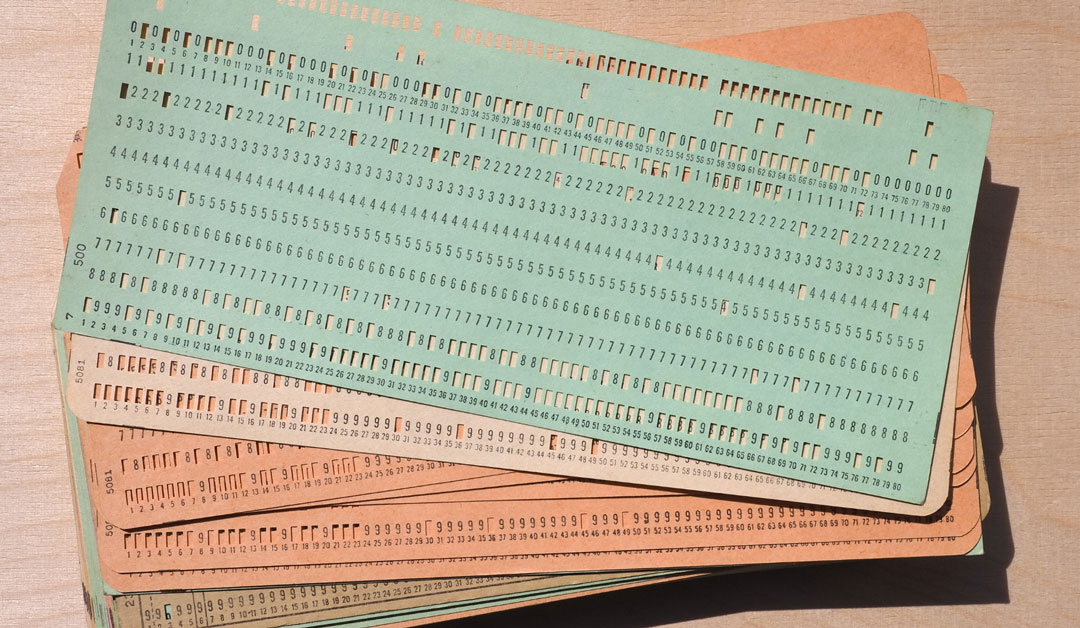

A reference to the punch cards used for programming in the 1980s. Photo: Shutterstock/Claudio Divizia

The articles in this series are presented jointly by DBS and content agency The Nutgraf. In the lead up to the bank’s 55th anniversary, The Nutgraf team interviewed 12 alumni to uncover these lesser-known stories about the bank in its early days, and its key contributions to a young and developing Singapore.

At first glance, they looked absolutely unremarkable. If not for the litany of numbers dotted across them, the flimsy-looking punch cards could have been easily mistaken for scrap paper.

But what these boarding pass-sized cards lacked in aesthetics, they made up for in application, being the core of a cutting-edge technology powering the game-changing Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) that DBS rolled out in 1981.

Before the existence of sophisticated coding languages like Python and JavaScript, these cards were the Excel sheets of that time. Vintage programming technology saw machines literally punching codes – typed manually on clunky keyboards – into them, before a punch card reader converted these physical codes into a virtual format. They would then be uploaded onto a computer as specific instructions for the ATM system.

And with an ATM only able to function with precise codes, these cards had to be painstakingly perfect. “If you find that the logic is wrong, we have to make the change. You find which card is wrong, pull it out, retype and get another card to replace it,” said Ms Cheong Yin Ping, one of the System Officers at DBS’ Computer Services Department then. “Can you imagine how manual the process was?”

The worst-case scenario? “You can’t mix them up or you die,” she added. “The programme is gone, and you have to re-type it.”

These were the teething tech pains experienced by DBS in its early years, as the bank looked to develop cutting-edge innovations to get ahead of the game. It was then the golden age of the analogue – a technology that typically relied on physical elements to transmit and process signals. Made antiquated today by the digital revolution, it was groundbreaking back in the 70s and 80s, and the fledging bank was quick to embrace it to better serve customers and be at the pinnacle of Singapore’s flourishing financial sector.

“During the early years, there were plenty of opportunities to experiment, to try new things,” said former Senior Managing Director Tan Soo Nan, who was at the bank for 29 years. “The introduction of new ideas, the catalytic work that we did, strengthened many parts of Singapore.”

The bank with no computers

With an array of gadgets like smartphones and laptops supporting DBS employees today, it seems utterly inconceivable there was once a time when the bank did not own any computers or even have an information technology (IT) team.

But that was a sobering reality in its early years when DBS was a tech greenhorn. It had to rent computer time from the Port of Singapore Authority (known today as PSA), which also helped build, deploy, and manage the system for the bank’s Savings Account. But to become Singapore’s pre-eminent bank, that dependence had to end.

This meant building its own technology capabilities, which the bank did in the 1970s by creating its first-ever IT team. “When we first started, it was only a few of us – a handful. It was a very flat structure,” recalled Mrs Teng-Han Soon Lang, who was part of the inaugural team that was a complementary mix of experienced heads and novices. No expenses were spared in teaching them the likes of system analysis and system design. “The bank didn’t stint on training… it was very comprehensive,” said Mrs Teng-Han.

So comprehensive in fact, that no computing background was required to join the team. “We hired new employees not because they had relevant degrees, but because they came from good universities with good degrees, and we were prepared to train them,” said Mrs Teng-Han.

With self-reliance as the ultimate aim, the team soon became competent enough to handle the Savings Account System previously managed by PSA, deploy a Current Account System, and achieve notable milestones.

“We did new things,” said Mrs Teng-Han. “We co-built the Current Account (system) and ran it on DBS machines, and we built other things on our own…the bank wanted to be innovative, so we looked at new types of technology and the way forward.”

Looking forward also meant charting new frontiers. In 1980, the IT team helped DBS deliver a show-stopping innovation: Autosave. The bank’s marquee programme saw customers enjoying the best of both worlds. They could earn interest with the money in their savings accounts, yet also get these funds automatically transferred to their current accounts whenever they had to draw cheques.

At a time when banks paid interest only for savings accounts, this two-in-one initiative was unprecedented – one that all banks in Singapore would eventually adopt to the benefit of all Singaporeans.

Making Autosave more remarkable was the fact that the young IT team had received little guidance when building the revolutionary programme. According to Ms Cheong, the instructions from the top were summed up in a single, straightforward phrase: go and implement this.

“So of course, we had to do it.”

Simple details usually taken for granted now – such as bank account balances following withdrawals – were built through tedious, meticulous processes. “We worked hard to make sure that the balances from the current account were correctly reflected in the savings account, and that they tallied,” added Ms Cheong. Autosave’s stupendous success would be the catalyst for more innovations to come.

Technology unleashed

Just a year later in 1981, DBS launched its very own ATMs. After Autosave, the bank promptly named these machines Autobanks. This was DBS’ reply to The Chartered Bank’s (known as Standard Chartered Bank today) setting up of Singapore’s first ATMs in 1979.

A DBS employee demonstrating how to use DBS Autobank to factory workers in 1984. Photo: DBS

Once again, the technology team played a vital role in rolling out this advanced technology of that era. They liaised with the current and savings accounts teams to interface the data and worked with technology company IBM – DBS’ main technology vendor – to understand how the machines worked.

At a time when customers typically queued at a bank just to withdraw money, the idea of a machine automatically churning out cold hard cash was simply jaw-dropping. “When we first managed to get the money out of the ATM, everybody in the computer room was clapping,” said Mrs Teng-Han.

Like Autosave, the versatile Autobank was revolutionary. A single machine could now allow customers to make cash withdrawals, cash deposits, enquire on account balances and transfer funds, among others. It heralded the era of self-service banking, said Ms Cheong.

Employees at the bank’s second computer centre in 1983. Photo: DBS

The Business Times in 1983 lauded its prowess, calling it “the tip of the electronic banking iceberg”. In less than five years, the bank had gone from tech novice to tech-savvy. “During that time, there was a push for innovations after our experience with ATMs,” said former veteran DBS employee Mrs Elsie Foh, who was with the bank for 36 years.

As the ATM got the technology ball rolling, another opportunity that DBS seized was to forever change the way people paid for things. In 1985, a consortium of five local banks – including DBS – set up the Network for Electronic Transfers (NETS), an electronic payment service provider. NETS saw cards overtaking cash as the main mode of payment, putting Singapore on the path to cashless transactions – a journey it is still on today. By 1993, spending through NETS surpassed the SGD 1 billion mark.

“That was also a great innovation,” said Mrs Foh. “We harnessed the capability of technology in a big way, and DBS has always been successful in this area.” In 1993, DBS even became the first bank in the world that allowed investors to subscribe for shares using ATMs.

Beyond playing a pivotal role in innovation, technology could even help mitigate potentially hazardous situations – even in the least expected areas. For instance, before the Stock Exchange of Singapore converted to scripless trading of securities in 1990, DBS had to store physical share certificates in a massive vault. “It was like a hive in a sense. A maze,” recalled former Managing Director of Securities and Fiduciary Services Nawaz Vilcassim. “Shelves here, shelves there, shelves everywhere.”

This posed a significant challenge. “When we closed the vault at the end of Friday, we were not allowed to open it till Monday morning,” said Mr Vilcassim. “My biggest concern was if a staff was inside. I did not want to take any chances, so I arranged bedding inside the vault, with food, water, and a telephone. In case they got stuck, they could survive for 48 hours!” Thankfully, the situation never occurred.

When physical certificates were no longer needed, DBS had to quickly adapt. The solution: to tap on technology. “We had to improve the technology and quality of the product that we gave,” said Mr Vilcassim. This led to the launch of IDEAL (International DBS Electronic Access Link) in 1991, a technology system that allowed its investor clients access to their portfolio information anytime.

“It was a big move for us,” said Mr Vilcassim. “It was developed all in-house together with our IT people. When we told the clients, they felt that we were on the ball in terms of developing new technology.”

Teething problems

While it got DBS ahead of the game, technology sometimes required a little troubleshooting, especially in the early days when the ATMs made their debut. To reduce downtime, DBS deployed the most advanced set-ups – such as a fault-tolerant computer system for its ATMs called the Tandem BASE24-atm.

A programmer testing a model of the bank’s first in-lobby ATM in 1984. Photo: DBS

Even if one or more of its components became faulty, Tandem still allowed ATMs to operate normally. This reliability meant that the machines could function 24/7, allowing the bank to serve its customers anytime – a considerable feat in those days. “For DBS, it was considered groundbreaking technology at that time… we were very, very proud,” said Mrs Teng-Han.

The early days of Tandem, however, saw some technical difficulties. Although the system ensured that the ATMs would not break down completely, the mainframe would inexplicably go offline daily at around 2pm to 3pm, as if it was taking a post-lunch siesta. It was an unexplained hiccup that left the technology team utterly perplexed.

“Every day, we had to restart the system to bring the mainframe back online,” said Ms Cheong. We had our own systems programmers, the IBM engineers and the Tandem engineers agonising over this.”

An employee monitoring the performance of the bank’s ATMs in 1984. Photo: DBS

Eventually, they discovered that the amount of time taken for an online system to process programming instructions had been set to 240 minutes, with the system shutting down after that time had lapsed. To think that the team had once attributed the issue to the supernatural! “We thought it was a ghost,” quipped Mrs Teng-Han.

But when technical issues arose, there was no finger-pointing. The soft power of camaraderie complemented the prowess of hard-hitting technology. “People were not blamed,” said Mrs Teng-Han. “We just understand why the problem occurred and put in measures to prevent it from recurring.”

This cohesiveness was fostered across the whole of DBS, within teams and between departments. Indeed, the strong ties between DBS’ retail banking team and their IT counterparts was crucial in helping the bank develop more innovative products for customers.

The two departments may have been markedly different, but they were unified by a common goal. “To service the customers better,” said Mrs Foh, who was Executive Vice-President of Retail Banking in the mid-90s. And although her job was a customer-facing role, she was also fascinated with the technical, backend aspect of these products and would even read up on the technology.

It also resulted in the retail team becoming technically competent. “Because we could understand the needs (of our customers), we could translate them and write out the user specifications in the way that the IT team could translate into IT specifications,” said Mrs Foh. “To quote one of my colleagues in IT, we were the darlings of the IT department.” This unexpected technical ability even led to the creation of a team within the retail department that specifically focused on IT innovations – the e-banking team – which acted as a bridge between IT and retail.

As the gap between the two departments closed, the doors for more innovations opened. Launching the likes of phone and internet banking services, and electronic banking kiosks firmly cemented DBS’ status as one of Singapore’s leading banks. It always stayed ahead of the curve.

“This was the work culture we had at the time, which is why to this day, we still have very fond memories about our work and our colleagues,” said Mrs Teng-Han.

Indeed, even the tediously manual punch cards are part of the cherished memories. After serving their sophisticated programming purpose, they would be then sold to the karang guni – to fund the technology team’s office pantry.

“We’d collect the money and buy biscuits to eat for teatime,” recalled Ms Cheong. “At that time, one carton of biscuits didn’t cost a lot. Sometimes you could buy two cartons!”

DBS was named the World’s Best Bank for five consecutive years. One notable characteristic where the bank stood out was its ability to leverage digital capabilities. This has earned the bank several ‘Best Digital Bank of the Year’ awards over the years. Our digital transformation journey continues to be studied as a model for digital transformation, with Harvard Business School being the latest academic institution to capture it in a case study.