breaking-new-ground

Breaking New GroundStandard bearer: DBS’ investments in financial industry professionalism

By DBS and The Nutgraf, 4 Aug 2023

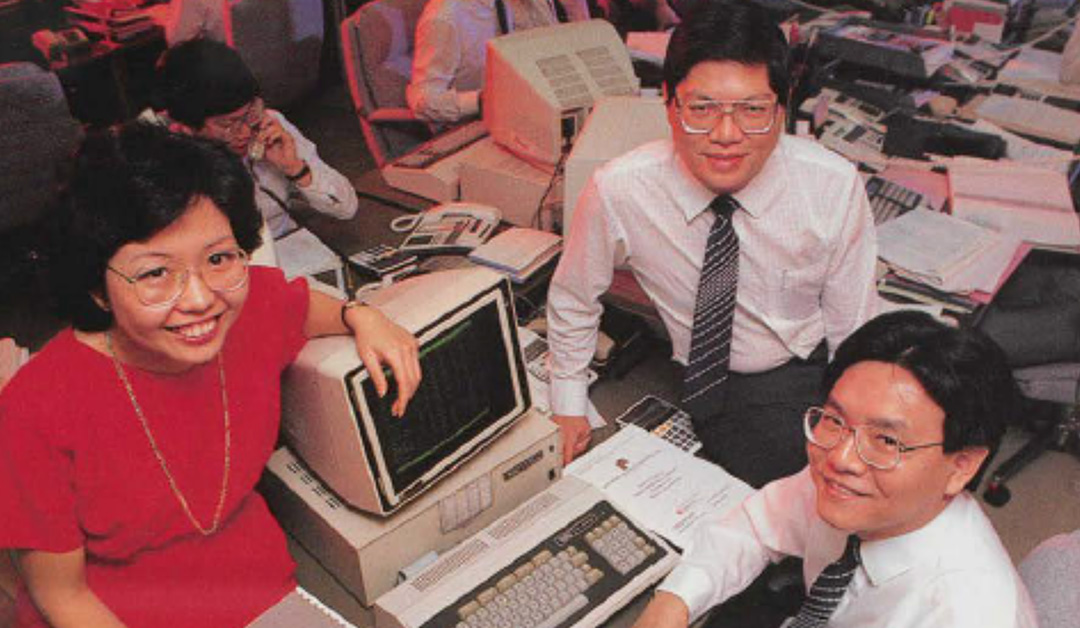

Mr Georgie Lee (second from right) with employees of DBS Securities and DBS Investment Research, during their discussion in 1986. Photo: DBS

The articles in this series are presented jointly by DBS and content agency The Nutgraf. In the lead up to the bank’s 55th anniversary, The Nutgraf team interviewed 12 alumni to uncover these lesser-known stories about the bank in its early days, and its key contributions to a young and developing Singapore.

On 2 Dec 1985, as the Stock Exchange of Singapore (SES) slammed shut to stem a two-day stock market freefall triggered by the shock collapse of Pan-Electric Industries, DBS senior executive Tan Soo Nan was called into an emergency meeting with the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS).

The MAS told Mr Tan and the top brass of the three other Singapore banks that this was a serious incident where the whole reputation of Singapore’s capital markets was at stake.

They needed the four banks to come to the rescue, by providing a “lifeboat fund” to help the stockbroking industry stave off risks of a liquidity crunch and avert a crisis of confidence about Singapore’s corporate disclosure standards.

This lifeboat would provide SGD 180 million in a standby credit line to prevent heavily leveraged stockbroking firms in Singapore from going belly-up, thus reassuring panicky investors that their brokers would still be able to fulfil their contractual obligations to clients.

These brokers, along with thousands of speculators, had punted on the shares of Pan-Electric (Pan-El), before it went bankrupt after failing to settle over SGD 450 million in debt.

“The brokers thought it was easy money: just roll over the forward contracts. Then Pan-El collapsed and all these contracts became worthless,” explained Mr Tan. “The brokers had a liquidity problem because a lot of the clients holding Pan-El shares could not top up their accounts.”

The lifeboat also included a contribution of SGD 6 million per bank, in exchange for which each bank would be given a seat on the SES. DBS was keen to obtain this stockbroking license, which opened up the opportunity to contribute to raising standards and professionalism in the financial sector.

“Our mission was very clear,” explained Mr Georgie Lee, who was recruited by Mr Tan to join the new DBS Securities unit. “The reason we are in this industry - it’s not just about making money; it’s about how we make a positive impact on the investment community as well as the public. Being DBS, people expect you to have a higher standard.”

Investing in the big picture

While profit maximisation was not DBS’ sole motive, its investments for the good of the country must still make money. This was the principle that DBS chairman Howe Yoon Chong made clear when Mr Tan came to him after the MAS meeting.

Mr Howe’s first reaction to the lifeboat fund proposal was characteristically pragmatic: “SGD 6 million? Why so much?”

“It’s for national interest,” responded Mr Tan. “I told him, this is the money that we have to deploy in order to strengthen the stockbroking industry, which is a core component of the financial market.”

Mr Howe bought the argument but threw in a challenge. “How long will you take to earn back this SGD 6 million?” he asked.

“With the right team, the right people, I’m very confident that you’ll get it in two years,” Mr Tan replied, without missing a beat.

With the top leadership’s blessing, Mr Tan set out to hire talent such as well-connected financier Peter Sutherland to head the new DBS unit’s institutional broking and research, as well as Mr Georgie Lee. The latter had serviced DBS as a client when he worked at broking house Lyall & Evatt and “had the experience and domain knowledge to give us a quick start”, said Mr Tan.

On 19 February 1986, DBS Securities Singapore opened with a dealing and administrative staff of 30, just one month after SES officially created four new seats for the Singapore banks. This was a move to “improve the standing of the local securities industry and inject a greater degree of professionalism”, reported the Business Times.

Instilling discipline

The aftermath of the Pan-El crisis resulted in new regulations that looked to reform the stockbroking industry. From stricter capital-to-asset ratios and prudent gearing ratios, these new rules were put in place to ensure sufficient safeguards for customers and brokers alike.

DBS enforced discipline on its brokers by implementing the required financial controls and benchmarks to curb the potential risks of over-leveraging. At the same time, it addressed a flaw in the existing trade settlement system by introducing limitations on its exposure to single customers, in line with new SES rules.

“Before the Pan-El crisis, a lot of customers traded without paying for the shares, which exposed the brokers to risks of customer default. Limiting exposure to a single customer was a very important step taken to help brokers avoid bad debts in the industry and shorten the settlement period,” explained Mr Lee.

“The Pan-El crisis shattered public confidence, so the new measures were needed to give people comfort that it's safe to trade on our Exchange,” he added.

Besides upholding standards, the new DBS outfit sought to improve the quality of research and investment advice, reviving the vision laid out by former Finance Minister Hon Sui Sen in 1973.

“Only by providing a better service in this direction can the investing public be educated and assisted in attaining the degree of sophistication and wisdom which will prevent their fingers being repeatedly burnt in fires of over-speculation,” Mr Hon had told the Business Times during the launch of the SES in 1973.

Unfortunately, this prescient advice was not fully heeded over the next decade.

The stockbroking business remained “very much about purely matching buyers and sellers”, rather than providing quality research and stock analysis, recalled Mr Lee. “They were very used to a free-for-all way of running business, relying on their gut feel or their judgement.”

Meanwhile, Singapore experienced what former DBS corporate finance veteran Kan Shik Lum described as an “IPO craze”, characterised by abundant liquidity, irrational expectations and opportunistic punters known as “stags”.

“People hoping to make a quick buck… when the shares were listed. It’s called the stag approach: apply for the shares, hope to get something and sell it once price goes up within a few days or a few weeks to reap that gain,” said Mr Kan.

Besides IPO punting, investors engaged in reckless trading of shares and instruments like forward contracts, which ultimately led to the stock market crash after Pan-Electric’s demise. “I suspect that many may treat shares as a gambling instrument. Pan-El has been a favourite because of its great volatility,” then-Finance Minister Richard Hu told the Business Times in a 24 Dec 1985 interview.

The Pan-El debacle exposed the urgent need to increase investor awareness and education – a gap that DBS sought to fill through various channels.

DBS took steps to hire experienced professionals – Mr Lee, for instance, persuaded some of his trusted former colleagues to join DBS Securities – while training new staff to provide well-researched, informed advice to both institutional and retail investors. Besides developing its own in-house research teams, DBS became the first Asian bank to use independent research from Standard and Poor’s on funds in 2004.

“There was an ethical responsibility on the part of our brokers to see how we could advise, educate the investing public,” Mr Lee said.

Knowledge is power

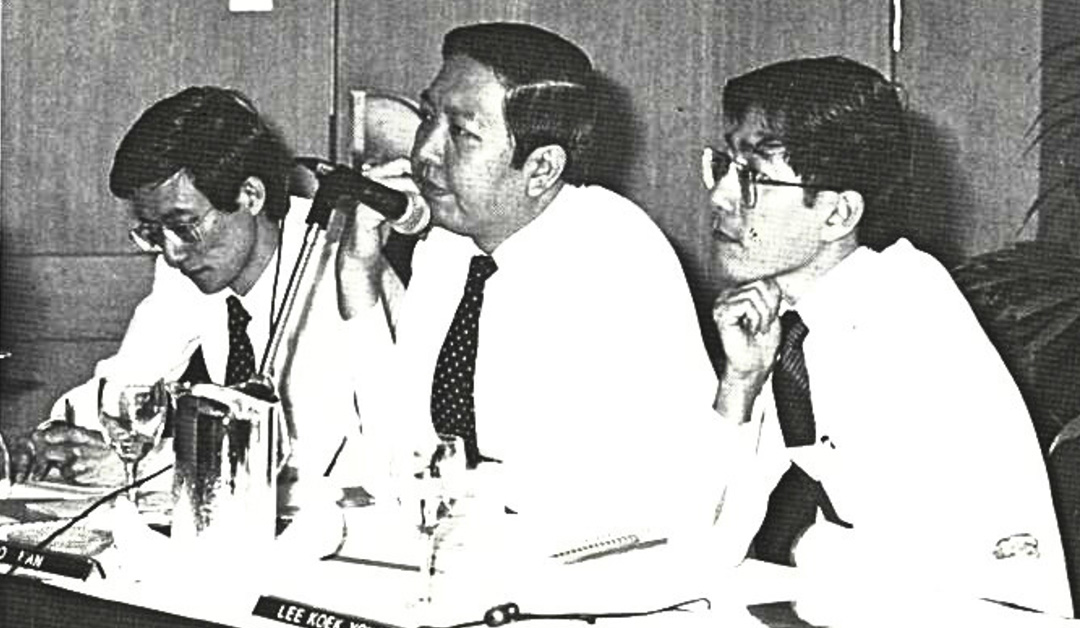

Mr Tan Soo Nan (middle) during the question-and-answer session at a seminar educating directors on SESDAQ in 1986. Photo: DBS

Investment talks were one way of quickly raising mass awareness among investors. And DBS relied on this format to quickly grow its presence.

For first-time investors, DBS organised seminars on hot topics such as “How to use CPF funds to invest in stocks”. The seminars were so popular in the 1990s that DBS Building’s 600-seat auditorium was reportedly jam-packed with 50 participants sitting on the aisles.

DBS also brought financial literacy to younger generations, conducting seminars in universities and schools and bringing back the iconic National School Savings Campaign in 2015.

The original campaign, which was first introduced in 1969 through POSB, cultivated values of savings and thrift in several generations of Singaporean pupils, many of whom have fond memories of collecting stamps to grow their savings.

DBS, which had acquired POSB in 1998, revived the much-loved campaign in 2015 with a fun new digital element – “Smiley Town”, a mobile gaming app which provides students with money saving tips and helps students track their savings. Over time, DBS added other digital initiatives such as the world’s first in-school wearable tech called “Smart Buddy”, to teach students how to save and spend wisely by tracking their financial habits digitally.

Besides advancing financial knowledge for Singaporeans, DBS also recognised the importance of training its own bank staff to provide transparent, reliable financial information and advisory services to customers.

In 1999, ahead of DBS’ launch of the Horizon unit trusts aimed at the mass affluent, the bank invested in a new training programme for its retail banking officers, many of whom had previously worked as bank tellers and were new to financial planning solutions.

Not only were the DBS staff trained to become competent advisors who could help Singaporeans identify and understand financial products that best fit their needs, these staff were also strictly warned against mis-selling and pushing customers to buy products that were not appropriate for their risk or investment profiles.

Pushy marketing tactics had been relatively common in the industry until the MAS introduced Fair Dealing guidelines in 2009 to ensure financial institutions provided customers with competent advisors, advisory services and appropriate products for their needs.

DBS’ 1999 training programme was an early precedent of its efforts to embed fair dealing practices across the organisation. Today, fair dealing is enshrined as one of the “Responsible Business Practices” identified as a key pillar of DBS’ sustainability agenda. This ethos is integral to DBS’ culture, noted Ms Choong Yang Ping, DBS’ Chief Operating Officer, Group Technology and Operations. “DBS has a reputation for being professional and forthright in all its dealings, perceived to be always by the side of customers to assist them when help was needed,” she said.

Passing on the integrity torch

Reputations are built over generations, and the values that form the bedrock of DBS’ reputation have been painstakingly drilled into younger generation of bankers since the early days of Singapore’s financial sector development when transactions were conducted using “chalk and dusters, strips of paper and snail mail”, recalled Mr Lee.

“No computers back then. We were transacting millions of dollars by just word of mouth. By the time the contract note was printed and sent to you, it was maybe one week later,” he said.

Without electronic records and technology, it was imperative to operate by the mantra, “Thy Word is Thy Bond”, said Mr Lee, referencing the London Stock Exchange’s motto. “It’s all about honouring your word. That was a very important value we learned as I sought to build up a whole team of brokers who were able to do well in the industry.”

One example of this ethos at work was the feat pulled off by two “very capable ladies in the Remittances department, who moved millions of dollars with very simple tools – just two landlines and a register book – within an intensive short window and with hardly any errors,” said Ms Choong.

Thankfully, technology and digitalisation have done away with those manual transactions, which would end up triggering a “high red alert” from the bank’s strong compliance processes today. But those ladies’ “commitment and tenacity to function under huge pressure” live on through the countless other unsung heroes who helped move DBS forward over the years, added Ms Choong.

This DBS ethos has shaped new hires who came from other corporate cultures as well, said DBS veteran Kan Shik Lum.

“One shocking proposal to me (from a colleague who had just joined DBS) was to ‘bait and switch’, meaning that we over-promise the client but under-deliver, or give them something very different from what we had indicated to them when the mandate was signed,” he recalled. “That’s something that we will not do in DBS, simply because that will impact our reputation, that will impact our integrity as well.”

These values are what kept Mr Kan working at DBS for 33 years, before he retired in 2015. “Everyone here was aligned with the mission – to provide quality service, to do what is ethical and right – and I felt at home,” he said.

The tradition of passing on DBS’ time-tested values to future generations continues today, because this is the best way to keep profiting from its initial SGD 6 million investment in 1985 to professionalise Singapore’s financial sector.