breaking-new-ground

Breaking New GroundBig City Dreamer: How DBS Land transformed Singapore from a third-world to first-world metropolis

By DBS and The Nutgraf, 2 Aug 2023

Caissons of the DBS Building in 1969, which later inspired the bank’s logo. Photo: DBS

The articles in this series are presented jointly by DBS and content agency The Nutgraf. In the lead up to the bank’s 55th anniversary, The Nutgraf team interviewed 12 alumni to uncover these lesser-known stories about the bank in its early days, and its key contributions to a young and developing Singapore.

Four imposing 7.3-metre-wide caissons rose from the depths of the mudstone and sand layers underlying the site of the DBS Building on Shenton Way.

The unique caissons, which formed the foundation of the Tower Block and would one day inspire the design of the DBS logo, towered over a group of perspiring building consultants in hard hats, who were scrambling to keep up with DBS engineer Wong Yui Cheong as he unleashed a litany of instructions while inspecting the construction site.

When Mr Wong finally ended the site meeting, the weary consultants knew better than to call it a day, recalled DBS veteran Lock Sai Hung.

“At night, Mr Wong would hash out the minutes to the meeting, assigning responsibilities to different consultants by fax. He expected replies by the next day,” recalled Mr Lock, who oversaw the bank’s property projects while the 50-storey DBS Building was being built from 1970 to 1974.

The project, which was unprecedented in height and scale, was the brainchild of DBS’ first chairman Hon Sui Sen. It required “a very strong character” like Mr Wong to complete it on time and within budget, said Mr Lock. “Some consultants said YC Wong was such a tough taskmaster, impossible to work for. But he got things done!”

Mr Wong and Mr Lock would go on to work on even more projects together to fulfil Mr Hon’s vision for DBS to play a foundational role in building Singapore’s Big City dreams. The bank would set new precedents for urban change by building icons like Plaza Singapura and Raffles City as well as one of Singapore’s first condominiums.

Learning from scratch

Under Mr Hon’s leadership, DBS started its real estate operations soon after it was established in 1968. Mr Hon and his successor Mr Howe Yoon Chong, who served as Chairman from 1970 to 1979, had very strong real estate experience and backgrounds. Their vision to stimulate the young nation’s development across a wide range of economic sectors, including real estate, shaped DBS’ property development mandate, said Mr Lock.

“So naturally, they wanted to take advantage of opportunities to build, such as shopping malls,” he said. “Their vision was to build big projects based on successful overseas ones like those in Japan.”

This vision gave birth to the idea of Plaza Singapura. The project was arguably the height of the industry’s ambition at that time: its high-end, family mall concept was unique but untested, and its location next to the Istana – “a very sensitive location”, as Mr Lock put it – posed challenges as the contractors had to be vigilant about noise, dust, and security controls.

As a development bank with strong government links at that time, DBS was in a unique position to liaise with the authorities as well as with the Istana to execute this project in compliance with their requirements. “Nobody except DBS could have done the project because only we had the ability to put in place so many security checks and precautions. We were trusted to do that,” said Mr Lock.

The idea for a well-managed, unified mall with Yaohan as an anchor tenant came about from observing the conflicts that arose between management and tenants of strata-titled private sector buildings on Orchard Road and Chinatown, said Mr James Ng, who served from 1973 to 1999 as a project manager at DBS subsidiaries, including DBS Land.

In such setups, different owners had multiple differing agendas for rental, upgrading and other factors, explained Mr Ng. “If rent was raised, some would go to the meetings – one guy brought a stick with him, some went with their lawyer. The chairman of the management committee may also bring his lawyer. We wanted none of that.”

DBS had a much broader agenda for Plaza Singapura than just selling it for profit: it wanted to create a successful lifestyle concept that would work and be replicated so that more investors would build similar projects in Singapore. Mr Ng’s team looked at models in New York, London and Hong Kong.

“We developed an instinct to know what was right, what was wrong. And we had to learn very fast, faster than the building was being built. In fact, we had to be months ahead of the building in our thinking, otherwise … trouble, said Mr Ng, who did not have a real estate background

“Many of the contractors available those days were quite ignorant of modern-day buildings, multi-storey buildings.”

“We had to coax, cajole, and work together with the contractor, concurrently learn and spearhead new avenues that Singaporeans and the team had never explored before.”

Ushering in the retail age

Plaza Singapura quickly became a hit with families, who would send their kids for music lessons at Yamaha music school while they shopped at Yaohan and have meals there.

The novelty of the mall, which boasted a wide array of high-end shops, became a tourist attraction. Prominent visitors back in the day would come to the Pan-West store in the mall to buy golf clubs, and “the Pan-West staff would then send an assistant down to the bank to get change because he only had big denomination notes”, recalled Mr Ng.

The success of the family mall concept, which was replicated in the heartlands with the opening of Thomson Plaza in 1979, showed that “having the hardware is one thing, but you need the software. You need people with specialised talents to make the whole thing work”, he added.

DBS Land constructed Thomson Plaza in the Upper Thomson Road area, which was then a latex drying area for the Lee Rubber Company surrounded by kampongs. The mall was situated here “to introduce suburban change – for people to buy necessities with dignity”, explained Mr Ng.

This dignified vision must have required quite a stretch of imagination for residents near the Thomson Plaza site, who had to put up with the stench of pig farms and swampy conditions whenever it rained.

When Thomson Plaza was completed, it boasted what was then considered futuristic designs like barrier-free access and three levels that were accessible from carpark lifts. This feature – carpark lots connected to each level of the mall – followed the precedent set by Plaza Singapura, which was one of the first malls in Singapore with this design. Thomson Plaza attracted key tenants such as Yaohan, Cathay restaurant and NTUC Fairprice.

To make the family mall concept successful, the DBS team requested for the authorities to cover up the large drain in front of the mall, inadvertently creating the forerunner of pedestrian walkways. This would benefit not just Thomson Plaza’s customers, but shoppers across the island as covered drains and walkways gradually become mainstream.

City within a city

Meanwhile, a new architectural vision was underway: Raffles City, which was envisioned to be an integrated complex comprising retail space, hotel, offices and a convention centre.

Construction for Raffles City began in 1981 after a decade of meticulous planning and study. And the entire process of building it took seven years due to its engineering and architectural complexity. Building the foundation for the 72-storey superstructure of the Westin Stamford hotel (today, Swissotel The Stamford), for instance, required 72 hours of continuous pouring of concrete.

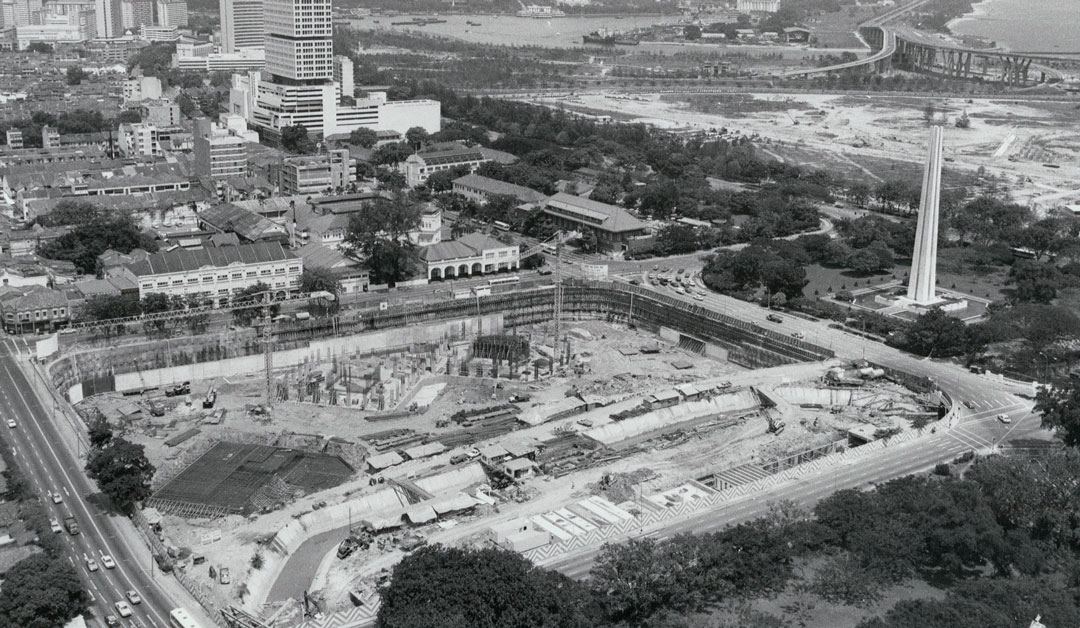

Aerial view of the Raffles City site in 1982. Photo: DBS

“We took about three days, three nights, and we were very lucky that there was no rain,” recalled Mr Loh Soo Eng, who spent about 15 years in various leadership roles in charge of real estate projects, including General Manager of DBS Land.

Covering up the open Stamford Canal next to Raffles City was another challenge. “That must have been one of the most difficult part of the project, because Stamford Canal has a lot of utilities connections, cables, and water pipes, among others. But now when you walk along Stamford Canal, you don't see it anymore,” said Mr Loh.

Mr Loh’s team also engaged traffic consultants to assess how many carpark lots would be needed for Raffles City, recognising that more shoppers would likely visit the mall using public transport once the MRT line was built. They then managed to persuade the authorities to allow them to reduce the number of basement parking lots in Raffles City to 1,200 from 3,000, thus avoiding the need to dig deep down to create such a massive underground parking lot.

When it opened in 1986 to great fanfare, Raffles City was credited for its “great foresight” in successfully introducing the Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions (MICE) concept to Singapore, which stimulated business tourism and enhanced the Lion City’s reputation as a premier base for large multinational companies.

Preserving Singapore’s heritage

More than just constructing buildings, DBS’ property subsidiaries played a role in creating some of the landmarks that would form an important part of Singapore’s heritage today.

One of the most famous icons is the Raffles Hotel, in which DBS acquired a substantial share in 1972. At that time, the Grand Old Dame was in disrepair and badly needed a facelift, so PMPL, a subsidiary of DBS, was appointed as project manager to restore the original façade. Recalling the meticulous restoration process, Mr Loh still marvels at the attention to intricate details, such as ensuring that the angle of the curves on some parts of the architecture was exactly the same number of degrees as the original building.

Another issue that the project managers mulled over at length was how to offer the public access to the grounds so they could admire the hotel, without letting the crowds wander into the inner Palm Court and disturbing the privacy of the hotel guests there.

“You cannot keep the crowd out of the jewel of Singapore,” said Mr Loh. “So you will see that going into Palm Court, there is a gate and only guests can go in with a key card, but the public can still view and enjoy. It was a win-win.”

Similar considerations about showcasing Singapore’s heritage and the distinctive architectural flavour of its colonial past guided PMPL when constructing luxury bungalows on various sites such as Swiss Club Road, Cluny Hill and Ladyhill Park in the early 1980s.

The Cluny Hill properties, which DBS’ property arm acquired from a trading company Straits Steamship, were English Georgian houses. Their architectural features included rigid symmetry in their central doors and window placements, as well as hip roofs and dormer windows. “They were tropicalised versions of noble English homes,” said Mr Ng.

But Singaporean pragmatism eventually overruled English sensibilities. PMPL chose to divide the sprawling plots of land into relatively smaller lots averaging about 10,000 sq ft, and some of the properties were sold at about SGD 1 million apiece at that time. Mr Ng recalled being questioned by an expatriate who used to live on a two-acre Cluny hill estate, “Why did you divide such a beautiful plot? I used to have good memories here.”

He responded, “I am sorry, sir. We are developers and our mentality is simple: maximum benefit for the maximum number of people.”

Spurring the private property market

In the same vein, expanding access to higher-end private housing for Singaporeans became an important objective for DBS’ property arm in the 1980s.

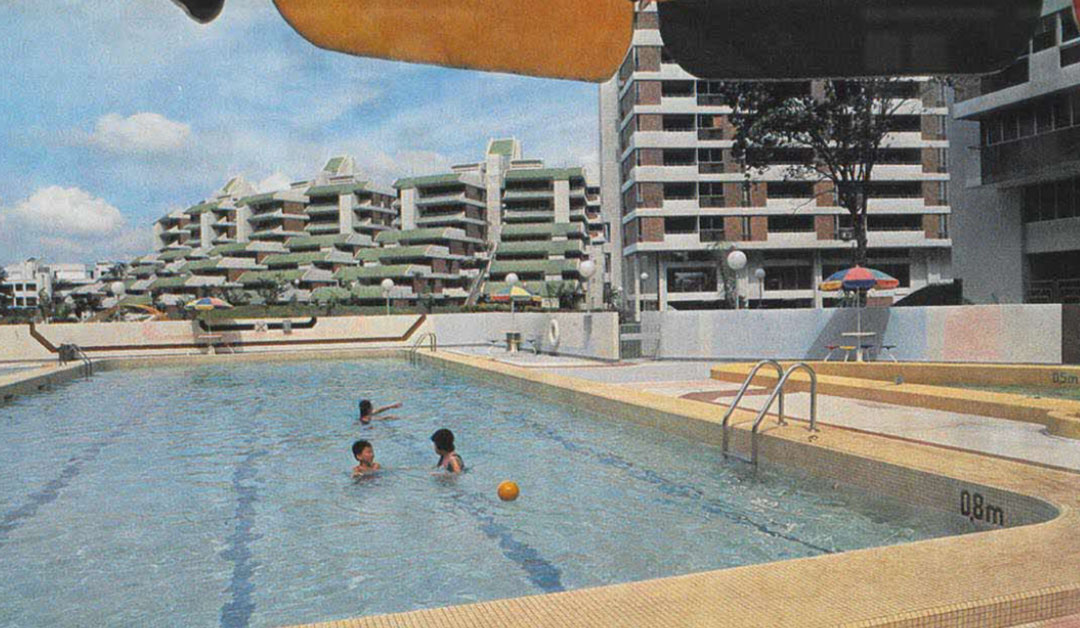

Pandan Valley introduced a new way of living in Singapore when it was launched in 1977. Photo: DBS

Pandan Valley holds pride of place as Singapore’s first and largest condominium when it was launched in November 1977. While it boasted an impressive array of facilities, including a kindergarten, a clinic, and various sports facilities, among others, sales were relatively slow. Less than 450 units out of a total of 605 sold one year after it opened for sale.

Amid sluggish conditions in the residential property market, it was initially “very challenging to market Pandan Valley” as private housing was a new concept for most Singaporeans at that time, recalled Ms Lim Sok Hia, who joined in 1979 and rose up the ranks to take on various senior management roles in the bank.

Undaunted by the initially cool response to Pandan Valley, PMPL continued to build more private properties over time, including Thomson Plaza residential units and Leedon Heights, which was the first property financing project Ms Lim worked on.

“At that time, condominiums were still in very limited supply, especially so called good-class condos like Leedon Heights. It was a relatively new segment then for Singapore,” said Ms Lim.

With Singapore’s economy growing rapidly, the middle-class segment would burgeon and the inflow of expatriate talent would accelerate. Sure enough, Leedon Heights enjoyed excellent sales and a condo-building frenzy ensued as private housing became increasingly sought after.

End of a property development era

As DBS expanded into a strong regional player over the three decades leading to the turn of the 21st century, its in-house property businesses were restructured several times for efficiency.

In 2000, as Singapore’s financial sector liberalised and it was deemed necessary for DBS to hive off non-core banking businesses, the bank exited its 24.9%stake in DBS Land. DBS Bank sold its stake to Pidemco, which shared the same core business as DBS Land, paving the way for the two merged entities to form CapitaLand.

But DBS’ imprint on Singapore’s city scape had been made. As a Straits Times commentary noted in 1994, projects such as Raffles City reflected the bank’s grand vision as well as its confidence in the future of Singapore, “symbolis(ing) the major role played by DBS Bank in both the nation’s economic growth and the daily lives of Singaporeans”.